I first encountered Toni Morrison 6 – 8 months after her death. I can’t remember how, but what I do remember was that it was solitary — in the thick of an emotionally stressful COVID-19 lockdown and an unnecessary ASUU strike. I found The Bluest Eye, her first book, and my introduction to her work, piled up in a folder of eBooks shared by friends.

Usually, complexity repels. Toni Morrison writes with the kind of complexity that draws you in. She’s one of the few writers whose work truly speaks to my experience as a woman, to my thinking, to my ever-growing quest against conformity. She writes about the ins, outs, and grey areas of the African American feminine experience. In other words, she doesn’t explicitly declare she’s a feminist or a civil rights activist. She doesn’t say that women face oppression like this or like that or that black people are oppressed like this or like that. She shows you through a very raw and true narrative, not watered down or linear, but like a web — because oppression is a web. She will show you what it means to be a person who contends with gendered, racial, and economic issues in a system designed to hate or love the characters in varying degrees. And you, the reader, are left to piece it together, interpret her message in the best possible way you can and apply it to your context. The Bluest Eye, set in Lorain, Ohio, between 1940 and 1941, is about Pecola, a black girl, her perception of beauty, and her search for acceptance in racist America. She doesn’t see herself as beautiful because her beauty is not white. The predominant culture at the time presented black women as masculine, contrary to the “feminine” white woman. The story gradually builds up to Pecola’s downfall, when her father rapes her, her parents neglect her, and she becomes mentally ill. It shows something that we so easily forget in today’s intellectually flattened climate that would, from then, inform my worldview: that systems are so powerfully poised to shape us and we must recognise this and ensure we do not lose our humanity in the process of this shaping, because we are all accountable for our actions, whether we like it or not. Pecola’s parents were victims of racism, poverty, and misogyny. Without justifying these monstrous acts, Toni Morrison is saying: Look, here’s the racist system that white people created to subjugate, here’s also the patriarchal system that men created to subjugate, and here’s the capitalist system that the government has designed to subjugate; Here’s where these systems connect and diverge; here’s how these black people travailed these systems, here’s how black people uphold these structures, and here’s the outcome of these subjugated systems on black people.

I mounted a series of rejections, some routine, some exceptional, some monstrous, all the while trying hard to avoid complicity in the demonization process Pecola was subjected to. That is, I did not want to dehumanize the characters who trashed Pecola and contributed to her collapse.

— Toni Morrison, The Bluest Eye, Afterword, p. 210 – 211

My realisation, then, was that even the most evil people in a society are victims of it and that we are all flawed, in part, by the systems within our society. Toni Morrison’s narratives aren’t singular. Beloved showed me the extent to which a mother’s love could do unimaginable things. Jazz explained why women stay with unfaithful and abusive partners, Sula and Love demystified the complexities of female friendships. God Help the Child revealed how mothers want to live vicariously through their daughters. Paradise depicted the conflict between a tradition that men so desperately want to preserve and a freedom that women want to embrace. Songs of Solomon illustrated the different class archetypes that exist within the black community, moving from “I want to be like white people” to “We must take revenge on white people through violence”. In the middle is the person who understands that a black person can never be a white person, but at the same time, it is pointless to pursue revenge. Tar Baby painted an accurate portrait of how couples become dysfunctional.

What I love about her work is that it has no single narrative and can be applied anywhere. You cannot simply call any of her books feminist or racial or American or economic. She is multidimensional. Meaning, each character (main or ancillary) lives in conjunction with the system, not in isolation from it, and you get to see how these systems shape their behaviours. In these very American/African American books, I have found pieces of myself. So, when I listened to her 1993 Nobel lecture on the 23rd of December 2025, I once again found some other pieces of myself.

Language. She talks about language. Language as crucial for narrative. Narrative as an important means of disseminating information. She talks about oppressive language and unmolested language. Oppressive language limits knowledge. Unmolested language “surges towards” knowledge. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language are forms of oppressive language that police mastery and discourage the mutual exchange of ideas.

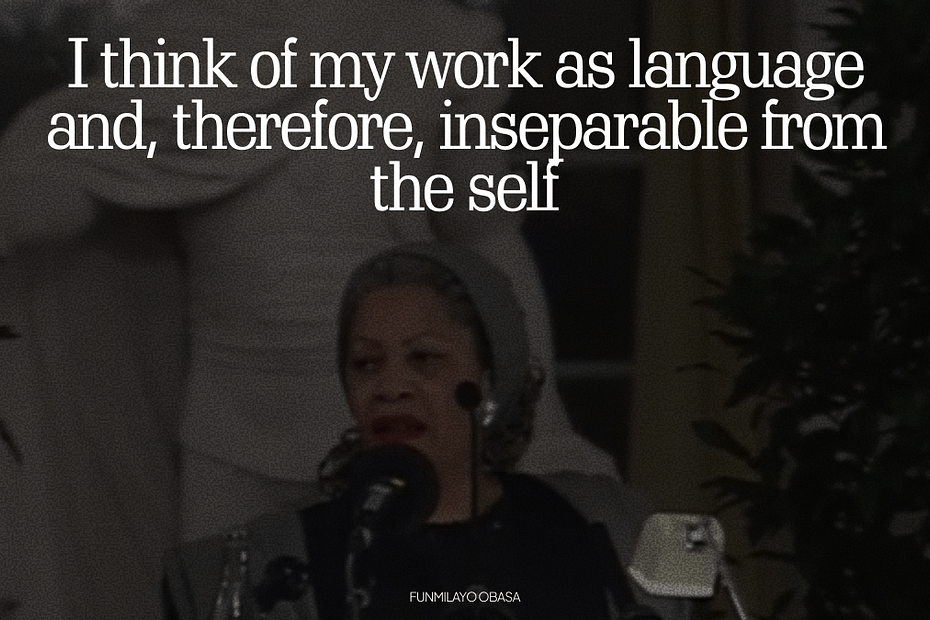

I could morph this into multiple interpretations, and I’m even forced to think of all the people I know that are enforcers of both kinds of language, but what sits top of mind is language as a means of expression, as a sometimes simple, sometimes abstract way of knowing identity & sharing identity. I’ve spent most of the year thinking about my work and the spaces it belongs to, who appreciates it and who dismisses it. What value it offers and where that value is most needed. I’ve spent a lot of time this year thinking about what work means to different people. For some, it is simply the path to financial agency. For some, it must stay different from the self. For others, like me, work is identity, and identity is multidimensional. I believe that is why I am drawn to people who speak about the work they do so deeply, people who see their work as a journey to perfection, change, self-awareness, not harm. I am drawn to people, like Toni Morrison, who can talk philosophically about their work, yet relate it to life as it manifests in the systems we reside in. I am drawn to those who speak unmolested language and fear and pity those who uphold oppressive language.

This is supposed to be an unplanned endnote for the year that I scrawled right before dawn. But rather than have it be a summary of my accomplishments and errors, I’d like to use it as an entry into the next. What I am saying against the backdrop of Toni Morrison’s idea of language is that the work I do is a form of language, and if language is an expression of the self, then work is inseparable from the self.